Home

Jars

Bottles Vases & Planters

Miniature Vases & Boxes

Tea Ware & Tea

Bowls Plates Dinnerware Sets

Incense Burners & Trays

Chopsticks & Rests

Music & Lacquered Boxes

Dolls & Figurines

Fans Mirrors Bookmarks

Masks No-ri-gae & Lamps

Celadon Pendants

Screens Souvenirs Phone Fobs

Furniture and Chests

Paintings

Handmade Only

About The Art of Korea

| |

Origins

Hidden between the demise of celadon and the

rise in popularity of white porcelain ware, Bun-cheong enjoyed about a one

hundred year reign as the most common type of pottery, and was used by both the

aristocracy and commoners throughout Korea.

The invention of Bun-cheong came about slowly more or less as an

evolution of the

Koryo Dynasty (918-1392AD) celadon that preceded, it rather than appearing

spontaneously and, as with

most of the developments in the Korean arts, forces outside of Korea played an

important role in its creation.

Celadon production flourished during the height of the Koryo

Dynasty where high quality vessels were needed for Buddhist rituals and by the

royal court. But the Mongol invasions into Korea which began in

1231, and the subsequent decline of the Buddhist culture which had led to Korea's

advancements in celadon production, began to take their toll as the populace

focused on survival rather than art. The quality of the celadon began to suffer

and more emphasis was placed on practical vessels that could be used by all,

rather than objects of beauty to be used by the aristocracy and in Buddhist

rituals.

|

From the

beginning of the invasions and for the next 150 years or so, the production of

vessels shifted from high grade celadon, to rather lower grade wares while still

maintaining some of the design features of celadon. The new pottery which began to emerge at this time was called Bun-cheong

and was made with a the same clay as was used for celadon, but of a noticeably

coarser grade.

During this transition period, attempts were made to dress

up the new wares and make them as attractive as celadon had been by

painting them with a celadon glaze which rendered a greenish tone to the wares. While the result was unique and attractive,

it could not compare with the beauty of celadon.

By the beginning of the Yi Dynasty (1392-1910) the production of

celadon had all but died out and the art of producing it was lost. Therefore, Bun-cheong

was the predominant pottery of this period and it continued to be the widely

produced and used for the next 100 years. |

|

|

Transitional period, Bun-cheong ware with celadon

glaze; rice bowl with lid. Late 14th to early 15th century.

Chun Hyung-pil Collection

|

|

As mentioned above, Bun-cheong was made with a coarser clay than

celadon and its techniques for production were a bit coarse as well. Earlier Bun-cheong

from the transitional period used a celadon glaze, and was often inlaid like celadon, but

later a

decoration technique unique to Bun-cheong was developed in which the the patterns

were formed with wood block stamps, or etched on, and

then the pieces were covered with a white slip. The slip was either painted by

hand, or the entire piece was dipped in a tray of slip after which the excess

slip was scraped off leaving it behind in the stamped or etched patterns.

Unfortunately, not all the slip could be removed this way and it often left a

whitish residue over the whole piece, or at the very least unwanted slip

outside of the patterns. Alternately, the white slip was brushed on using a

rough brush in a carefree fashion and, though not particularly precise, this

method was quite popular both in Korea, and out. In short, Bun-cheong was of a rougher finish than

celadon both due to the coarser clay and the level of craftsmanship.

Many different patterns were used to decorate Bun-cheong

but among the most common were the "rope curtain pattern", and pattern of

stamped chrysanthemum heads, or plain dots.

|

|

|

Bun-cheong bowl with lid and a rope

curtain

pattern. Mid 15th century.

Ho-Am Art Museum

|

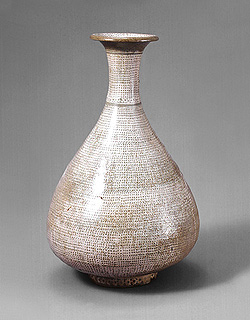

Bun-cheong wine bottle with a stamped ring of

chrysanthemums above

the band on the neck and on the base, and a rope curtain pattern

over the rest of the body. 15th century. National Museum of Korea

|

As with the introduction of Bun-cheong,

its decline was also brought about by foreign influence. The Japanese invasions

into Korea by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, which began in 1592, razed the country of its

cultural treasures; a great many of the temples, palaces and other culturally

significant structures were destroyed by the Japanese and the populace was

either displaced or killed. Many of the pottery kilns that had been operating

throughout the country, were also destroyed or shut down by the invasions and

the potters themselves were taken back to Japan to bolster the Japanese pottery

industry that was to become so famous in later years.

In the years prior to the invasions, the Korean potters had

been improving the craftsmanship of Bun-cheong wares and developing white

porcelain as well. But the loss of many of the Korean potters dealt such a

severe blow to the

development of Korean pottery that after the end of the Japanese invasions in 1598, the Korean

ceramics industry never recovered completely, and though the production of white

porcelain did re-appear, the production of Bun-cheong did not. While its

manufacturing techniques were considered to be "lost", it is more

likely that the emphasis simply shifted to the production of superior white

porcelain wares and that the inferior Bun-cheong wares were no longer

needed.

The years immediately following the Korean war (1950-1953)

left little time for cultural reminiscing, but starting in about 1955, the same

time that Korean artisans began to rebuild the celadon industry, they also

re-kindled the production of Bun-cheong.

The transitional period of Bun-cheong in which celadon

glazes or celadon style designs were used, is not well represented in modern Bun-cheong. Most modern Bun-cheong still uses the coarser clay it was

originally created with and incorporates many of the design features used during

the height of Bun-cheong production; most notably the rope curtain

pattern, and stamped chrysanthemums and dots. Its finish is generally a brownish

glaze which often has a dark green tint, and its stamped patterns are filled

with a white slip. Not as culturally significant as celadon, it is produced by

fewer artists and in limited quantities today.

|

|

|

Modern celadon jar with lid and rope curtain pattern.

Korean-Arts' item BCJ008

|

Modern celadon cups with stamped chrysanthemum pattern

around the top of the cup body, and a rope curtain pattern over

the remainder of the body. Korean-Arts' item BCCS011

|

|